It is time for parents to teach young people early on that in diversity there is beauty and there is strength. We all should know that diversity makes for a rich tapestry, and we must understand that all the threads of that tapestry are equal in value no matter their color.

—Maya Angelou

One night Drew came to me frightened, desperate, broken. It was a look that was all too familiar to me. A look that I knew would require my full attention and support. He needed his mom, he needed to be heard, and he needed to trust that I would know what to do. He said six powerful words: “I need to be someplace safe.”

Midway through tenth grade, Drew had begun living at home and at the Q Center as a male. He was back to wearing men’s clothing and got his hair cut short. We were using male pronouns and his preferred name “Drew” instead of his birth name. Although he wasn’t out as a male to anyone outside our family or the Q Center, he could feel things already starting to turn around and get better.

He felt ready to share his identity with others.

Others; however, were not as accepting and understanding. Life started to feel overwhelming again. He felt that no one really saw him as a guy—and he feared they never would. It began to take its toll on him. Even with countless hours of therapy and numerous medications, his anxiety wasn’t getting any better. It became too much for him to handle.

Drew had given up hope and felt he’d rather die than continue the struggle. Thankfully, he recognized this emotional place and what he was contemplating. He remembered the key words to say when he came to me that night. “I need to be someplace safe.” I knew exactly what he meant. After a quick consult with Drew’s therapist, I had a plan.

I let Vince know what was going on, and then I took Drew to the pediatric emergency room at Golisano Children’s Hospital. Vince and I both knew not to argue when Drew said he felt more comfortable going with just mom.

It was a miracle break-through that Drew was able to come to us at all. I don’t know if this was Drew’s first suicidal ideation since his attempt nearly two years earlier, but this is exactly what we wanted to happen when the thoughts came back. Drew was fighting along with us, not hiding from us.

Hospital and social workers will want to pay attention here.

Golisano Children’s Hospital got it right. The human experience there was life-changing for Drew, as well as for Vince and me. We learned over the next few days (and weeks) how important it was to embrace the discovery process that was going on within Drew. We, as parents, would watch our child truly open up. Finally.

A social worker assigned to take care of Drew was an angel in disguise. She performed the intake interview and assessed Drew’s state and reason for feeling suicidal. Drew looked to me to answer the questions that were difficult for him. I fumbled for the right words as I tried to explain that although Drew is a girl, he feels more like a boy than a girl. I explained that he had been living as a boy at home for more than a month but had just started expressing himself this way to a few friends and others outside our home.

The social worker knew all about transgender youth. She was so supportive and knowledgeable. She immediately “got” the male pronouns and called Drew by his preferred name. Drew was visibly relieved that we got to speak with someone who actually knew what he was talking about. Soon he relaxed and answered questions himself, rather than look to me. For me, it was so comforting, consoling, and satisfying to see that my son was able to speak and be heard, when the person he was speaking to was able to see him and affirm who he really was. Who knew we would find an ally like this in an emergency room?

Vince and I had never used the name “Drew” outside of our home before. I was uncomfortable and fearful of how this would all play out. This particular social worker was one of many allies and angels placed along our path to help us. She informed the rest of the staff of Drew’s preferred name and pronoun usage, and the staff took it very seriously. I didn’t have to educate anyone who interacted with Drew and be the corrector of pronouns—an experience that always made Drew shrink and withdraw. I didn’t have to advocate for my son with every new nurse and doctor who saw him. Instead, I was free to just be Drew’s mom.

Drew responded well and things improved quickly. It was the first time Drew was actually accepted by the outside world and it seemed to give him hope. He was delighted to hear his name, a name he had chosen. I remember the friendly staff person who would arrive with his breakfast tray and cheerfully say, “Good morning, Andrew. It’s going to be a good day today. I hope you enjoy your breakfast!” The lab technicians who collected Drew’s blood, the nurses who tended to him day and night, even the kind men and women who cleaned his room and emptied his trash—they all called him Andrew and used male pronouns.

It’s important to note that the actions of the doctors and staff conveyed the message that a respected authority acknowledges and validates the basic transgender human condition. Up until this point, validation had only come to us from the Internet, the Q Center, and books.

For Vince and me, it was a pivotal time to watch others affirm our son—using his preferred name and male pronouns. We were able to observe the effect it had on Drew. He arrived at the hospital feeling hopeless, thinking the world would never accept him for who he was, and wanting to end his life because it was too hard to pretend to be somebody he was not. He arrived shaking, crying, head down, and unable to look even me in the eye. I watched the tension, fear, and pain disappear as Drew began to relax. It paralleled his first day at the Q Center.

As we observed Drew’s reaction toward the simple acts of others affirming him, we realized that our job as parents extended far beyond providing a safe home. It required us to support him in getting to a place where others would see and know him as a male. He needed to be who he truly is, and we needed to help make that happen.

In a private conversation, the social worker told me about her experience in Philadelphia working with transgender youth. Her words added an ingredient to my growth; she validated what I already knew intuitively—that my son’s condition was very real and very serious—but there was also help and hope. She told me about an annual conference in Philadelphia that provided comprehensive education on transgender issues, free of charge.

Drew spent four days at Golisano Children’s Hospital waiting for a bed to become available at a nearby psychiatric hospital. We were insistent that Drew be sent to Four Winds; a healthcare facility we were already familiar with and personally give two thumbs up.

The trip there was an uncomfortable three-hour ambulance ride, but I was grateful I could ride with Drew. It’s a surreal experience to sit in an ambulance with my son and look back through the rear window to see Vince, alone and following in our car. Two years earlier, Vince and I were following Billy in the ambulance after Billy’s suicide attempt. I remember the worry and hopelessness we felt on that long and silent ride. As I looked back at Vince, I thought how lonely and scared he must feel. I looked down at Drew who was lying with his head in my lap, holding my hand, and thought he, too, must feel lonely and scared. We will get through this, I thought. Four Winds helped Billy, it will help Drew.

The intake experience at Four Winds was just as we had expected. Adam, the therapist who interviewed the three of us not long after we arrived, was knowledgeable and skillful when asking Drew questions. Drew was open and engaged in the conversation. I smiled inside.

While at Golisano’s, Vince coached Drew to be an active participant in his own health and wellness. Vince used the example of Drew’s last pair of eye glasses. Drew had noted how good his prescription was. Vince pointed out that the lenses were so good because Drew took his eye examination seriously—something only he could do. Drew’s previous glasses lacked visual clarity because an impatient Drew didn’t see the importance of taking the time to select the correct lens during the exam.

Drew took the advice and was now vested in the process at Four Winds. Adam also made it easy. He was able to relate with Drew, interpret his feelings, and repeat them back accurately. Their dialogue was genuine, honest, and clear. It was fascinating to watch.

In the past, Drew would become so frustrated whenever Vince and I tried to verbalize what we thought he was feeling. I think it pleased Drew that we could be there to witness the discourse between him and Adam, to see it firsthand.

Over the course of his two-week stay, Drew was feeling validated, and I too walked away with a new confidence, building on the experience at Golisano Children’s Hospital.

It was hard for me and Vince to accept that we couldn’t help Drew ourselves. We had to depend on experts outside our family, just as we had with Billy. We did the best we could to select the professionals, programs, and facilities to help us and our children, but ultimately, we had to turn it over to the experts and let go. The Serenity Prayer reminds us of this every day as we pray for the serenity to accept the things we cannot change, courage to change the things we can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

We left Four Winds with something we didn’t expect or even know was a possibility—a formal diagnosis of Gender Identity Disorder (GID), the term used by psychologists and physicians to describe persons who experience significant gender dysphoria (discontent with the sex they were assigned at birth and/or the gender roles associated with that sex). It was as if Drew became officially transgender. For me and Vince, it was certainly easier to explain to people now that we had a formal, medical diagnosis.

The DSM-V, the newest edition of the psychiatric diagnostic manual, which was released in May 2013, stopped labeling transgender people as “disordered.” The DSM-V replaced the diagnostic term, “gender identity disorder,” with the term, “gender dysphoria.” Based on standards set by the DSM-V, individuals will now be diagnosed with gender dysphoria for displaying, “a marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender.”

Drew never returned to his classes after he came home from Four Winds. The high school graciously provided homebound instruction for the remainder of tenth grade.

Drew continued to attend the regular LGBT youth meetings at the Q Center, but also began attending the monthly TransYouth group meetings. These sessions taught Drew about gender identity and how it is completely different from sexual orientation. He also got to know many other transgender youth just like him.

After an initial meeting at the Q Center, Drew told us about an interaction with a guy he met there. Drew had asked if the guy used to be a girl. This was back before he knew the language and what was appropriate, offensive, or insensitive. Now, the notion ‘used to be a girl’ doesn’t make sense or even sound right.

The Q Center is a safe space and Drew’s language problem was overcome with time. What’s great is that the Q Center has programming that helps kids learn the vocabulary and facts. Drew finally started connecting the dots in his life. We did, too.

Although he had always felt like a boy, Drew was able to live with a female body because it wasn’t an issue before puberty. In his mind, he was attracted to more boyish things. He always wore male clothes. It was never a big deal. When puberty hit, the problem then became acute because now things were happening that definitely contradicted his sense of who he was. His body was changing and betraying him. Drew realized that he was transgender.

Gradually, Vince and I made friends with adults at the Q Center. We found it was a safe place for us, too. LGBT, much less transgender, was all new to us. It was scary in a “fear of the unknown” sort of way. The parents, staff, and volunteers at the Q Center were excellent supports for us. After Drew came out as transgender, we started attending the TransParent group at the Q Center, a support group for parents of transgender and gender non-conforming youth.

At our first TransParent meeting, we met Karen and Jason. What struck me about this couple was how much they embraced their child and their child’s gender identity. They were quintessential role models. They taught us how far we could go, how supportive we could be, and how important it is to advocate for your child. Their relationship with their child was beautiful. A lot of our fears and uncertainty were counterbalanced by Karen and Jason’s positive experience. We saw a place of normalcy and true acceptance in our future—hope beyond our current fears of the unknown.

Months later, when the Q Center’s program coordinator left the area, Karen and I became co-leaders of the TransParent group—a responsibility we still share. I am committed to being there for other parents, as Karen and others had been there for me. For a while our group was very small, but it has since steadily grown.

The Q Center has played an important role in our lives, providing a safe place for our son while serving as a catalyst for our own growth. While connecting us with friends and resources, the Q Center also merges merriment and a playful spirit. A beautiful example of this is the Pride Prom, a formal dance put on each year by the Q Center.

At the Pride Prom, kids can attend with whomever they want. If a guy wants to bring a guy, he brings a guy. If a girl wants to bring a girl, she brings a girl. They can wear whatever they want and express their identity. Many kids find their high school dances restrictive and intolerant. Recall before Drew’s transition, he was not allowed to enter a dance because he didn’t wear a dress.

In the three years Drew has been attending the Q Center, we have seen that the kids really look forward to the Pride Prom. It’s a very good thing. Drew’s first experience was priceless.

When Drew first told us about the prom, he asked if he could get a suit. This was after years of never wanting to go shopping for clothes. I remember the moms of Drew’s friends often telling me how lucky I was that my child didn’t live at the mall and didn’t constantly beg me to take him shopping for new clothes, shoes, jewelry, make-up, and hair accessories. Don’t get me wrong, I believe in expressing and being grateful for what you have, rather than dwelling and yearning for what you don’t have. However, it never felt right to be grateful that Drew avoided malls. It wasn’t that he was content with what he had; rather, he was hiding from the world. I always felt like we were missing a normal, healthy experience with our teenager.

So here I was being presented with a request to get a suit. And what did we do? We went shopping! I cried in JC Penney. Drew was trying on suits and having so much fun. He would come out of the changing room and look at himself proudly in the three-way mirror. He modeled and showed himself off. He was really excited. He struck pose after pose and just strutted around, “Hmmm, should I wear a vest? Let me try this vest on. I think I like this vest. Should I do suspenders?” He loved what he saw in the mirror, and so did I.

I was crying because for years Drew wouldn’t look in a mirror. He hated the mirror. He had such dysphoria; what he saw in the mirror caused him such pain. It makes sense now because someone presenting as a girl was reflecting back at him and this was not what he felt like inside. When he saw himself in a suit, the guy in the mirror finally matched what he felt inside. He liked what he saw. He saw a guy trying on all these different suits and it felt right. By the way, he looks darn good in a suit!

I can’t say the excursion all went perfectly, though. Drew still had a female body. Unlike a male’s body, he was curvy, and his shorter stature made it more difficult to find pants that fit him right. Drew wore a binder to flatten and conceal his chest. His binder showed through some of the shirts he tried on, so he had to make adjustments. Overall, however, it was a joyful day—especially for the mom who had been waiting fifteen years for an occasion like this!

Fast forward to prom night when Vince and I dropped off Drew. The prom was at a hall in an unfamiliar part of town, but we were learning to let go and trust more. We appreciated how the staff at the Q Center knows how vulnerable the kids are and they are very protective. We returned to pick Drew up just before the prom was about to end. We texted him so that he knew we were waiting. We saw him saying his goodbyes, hugging at least twenty people. What parent’s heart wouldn’t be warmed by such a sight?

As he walked toward the car, I watched him. I was just fascinated. He seemed so relaxed, confident, and happy. Could this be the same boy that was so broken only a few short months ago? The boy who couldn’t hold his head up, couldn’t look anyone in the eye? Now, he walked tall and proudly.

I looked a bit more closely. He had a crown. I remember asking Vince, “Do you see that? He’s got a crown. What do you think that crown means? Why’s he wearing a crown? Are they all wearing party hats?” I looked around thinking they just put party hats on, but nobody else was wearing a hat or a crown. “What do you think the crown means?” He also had all these beads around his neck. He had so many beads it looked like Mardi Gras. He had so many, you would think he would fall over. The other kids didn’t have the beads. What was up with that?

He and a friend finally got in the car. Half-jokingly, but silently hoping, I had to ask, “So what’s the crown? Are you prom king?” Drew said, “Yeaaaah!” and got this big smile on his face.

I later learned the prom organizers gave each of the youth two strings of beads when they arrived at the prom. They were each instructed to put one strand around the neck of the person they chose as prom king and one around the neck of the person they chose for prom queen.

I let my understanding of what had happened sink in. All of those beads around my son’s neck had been placed there by his friends; by the dozens of peers in attendance who chose him to be their prom king.

It’s painful to think back to the time when he was so lost and alone. He didn’t have many friends. He didn’t want to be around anybody. Now, he was voted prom king by his friends and other kids he met there that night. I still get a warm flood of goosebumps when I think of that moment. As a mom, I am overcome with feelings of love and gratitude for those young people at the prom who lifted up my son when they placed their beads around his neck, and to the many allies and angels who led us to this place.

What is Transgender?

When Vince and I first learned that our son’s years of depression and anxiety might stem from an inner struggle with his gender identity, I rushed to learn all I could. I performed Google searches, watched and read personal accounts of transgender people, sought transgender studies, read every book I could get my hands on, and consulted with doctors, professionals and experts. Here’s what I found.

Essentially, transgender people challenge traditional ideas about gender and defy social expectations of how they should look, act, or identify, based on their birth sex. Transgender is an umbrella term used to encompass individuals, behaviors, and groups whose gender identity or gender expression do not conform to society’s expectations of what it means to be male or female. Many identities fall under the transgender umbrella, including transsexuals, cross dressers, drag queens and drag kings.

Transgender is often shortened to trans. Trans or trans* is an abbreviation that began as a way to be more inclusive or concise in reference to the different identities that could be referenced by using the term. The asterisk implies that trans* encompasses transgender, transsexual, and other transitional identities challenging the gender binary.

Transsexuals are people who experience an intense, persistent, and long-term feeling that their body and assigned sex do not match their gender identity. Such individuals desire to change their bodies to bring them into alignment with their gender identities.

The term transsexual comes from the medical establishment and many people do not like this term. I’ve been told it can be an “ouch” word and is not a term I should impose on people. However, there are some people who prefer the term transsexual, such as my son.

As I tried to understand all I was reading, my head was spinning. There was a lot of terminology, much of which didn’t make sense to me at the time, and some of which made me uncomfortable.

At first, I got hung up on phrases like, “challenging traditional ideas” and “defying social expectations,” because to me, those words implied a chosen behavior of an individual to defy or rebel against society. This clearly was not a chosen behavior on my son’s part. I know this and I can tell you this with absolute certainty that he did not choose to be trans—nobody would deliberately choose such a hard life in our society.

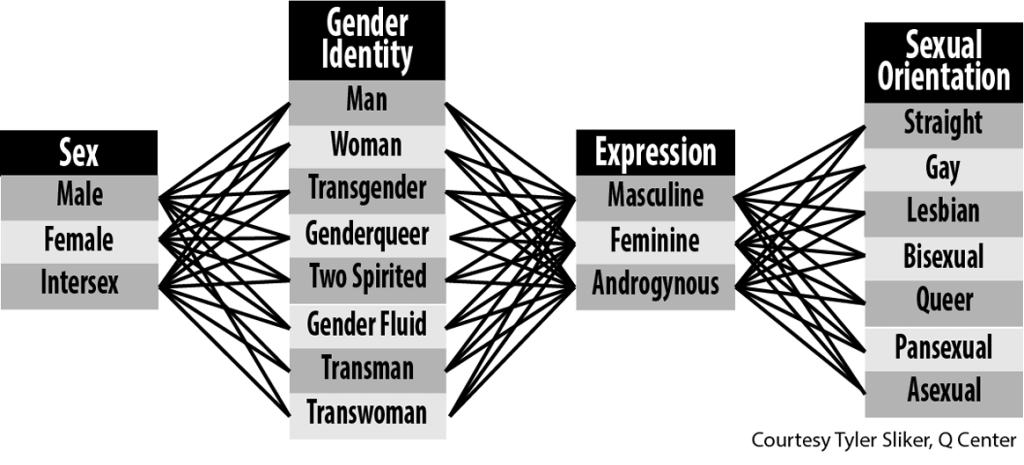

At awareness training and workshops, we often start out by explaining the difference between sexual orientation and gender identity, and then define each of the following separately: birth sex, gender identity and gender expression. When these terms were broken down for me, it became easier to understand and explain them to others.

Before expounding further, I’m going to oversimplify in a non-scientific, non-textbook way just as somebody once explained to me. They said, “Terri, your child has a male brain inside of a female body.”

Many of us think “penis = boy and vagina = girl.” Most of the time this turns out to be the case, but not always.

Numerous studies have confirmed the long-held suspicion about the brains of males and females. They’re not the same. Scientists now know that sex hormones begin to exert their influence during development of the fetus. I won’t bore you with the studies and the brain imaging technology used to capture and analyze the differences, but if you want to confirm for yourself, the findings are out there.

What I had always assumed; however, was that a penis and a male brain came as a matched set, just like a vagina and a female brain were supposed to be a matched set. It does not always turn out that way.

A child can be born with a variety of unexpected, uncommon or undesirable traits. For example, an extra finger or missing toe. Similarly, a child can be born with missing organs, a malformed heart, an undescended testicle, a missing testicle, or a variety of other unusual traits, which some may call “birth defects.” I personally don’t like to imply that being born transgender is a birth defect, although my son refers to his condition as a birth defect. I respect that certain terminology can influence reactions—what may be offensive to some can be acceptable to others—and I offer this example with the hope that it helps clarify my point.

My child was born with a male brain inside of a female body. There are different theories and studies that explain why and how this happens. Briefly, some believe a hormone imbalance during fetal development causes an individual’s gender identity (what is in their brain) to not match their biological sex (what is between their legs.)

At first, these concepts of mismatched gender identity and biological sex were difficult for me to grasp because I had always lived in a body that was aligned with how I identified. When I was born, I had a vagina and I was labeled a girl. This wasn’t a problem because I always felt “like a girl,” dressed “like a girl,” acted “like a girl” and was happy to be a girl. My sex and gender identity were a matched set. They were aligned. For most of the population, our sex and gender identity are aligned, so this can be a challenging concept to comprehend.

I committed my time and energy to understand so I could best support my son. The reality is I could spend a lifetime studying the causes, diagnostic criteria, and variations, but I had to make decisions now. There was enough information and research to convince me that being transgender was a legitimate condition.

What is someone’s sex? What is someone’s gender? What is the difference between sex and gender? Think in terms of what we’re born with versus what we learn. Everyone is born with a birth sex, and everyone develops a gender identity.

It is helpful to grasp a couple key concepts:

- • The distinction between birth sex, gender identity and gender expression, and

- • The distinction between sexual orientation and gender identity.

Birth Sex

Your birth sex could be male, female, or intersex (having both female and male sexual characteristics). A label of male or female is assigned at birth based on the appearance of external genitalia, and this is the sex designation that appears on birth certificates and other legal documents. Chromosomes are another way of labeling birth sex, although most of us don’t have our chromosomes tested and verified at birth. A child born with a penis is assigned the birth sex male (and is assumed to have two distinct sex chromosomes, XY.) A child born with a vagina is assigned the birth sex female (and is assumed to have two X chromosomes.) Intersex people have various combinations of sex chromosomes, hormone levels, and genitalia.

Birth sex refers to the physiological and anatomical characteristics that a person is born with or that develop with physical maturity, including internal and external reproductive organs, chromosomes, hormones, body shape, and genitals. Birth sex is also referred to as “assigned sex” or “biological sex.”

Gender Identity

Your gender identity is your internal sense of being male, female or gender non-binary. Gender identity is “between your ears” whereas birth sex is “between your legs.”

Gender identity, a person’s own understanding of themselves in terms of categories like boy or girl, man or woman, transgender and others, is how a person feels inside—what they believe themselves to be.

An individual understands their gender identity much earlier than their sexuality. By ages two and three, children begin noticing the difference between being a boy and being a girl, and they start to identify with one or the other. Some studies show gender-typed play begins as early as eighteen months.

Gender Expression

Gender expression is behaviors and lifestyle choices that convey something about a person’s gender identity, or that others interpret as meaning something about their gender identity, including clothing, hairstyle, mannerisms, communication patterns, social roles, etc. We often categorize gender expression as being masculine, feminine, or androgynous.

Your DNA doesn’t determine how you style your hair or what clothes you like to wear.

Gender expression is not binary (that is, it is neither exclusively masculine nor feminine) and it is not necessarily aligned with birth sex or gender identity. For example, a man can be masculine or feminine just as a woman can be masculine or feminine. Furthermore, all people can fall somewhere on the spectrum between masculine and feminine, and where they fall can change from day to day.

Sexual Orientation

Your sexual orientation equates to your physical, sexual and/or romantic attraction to others. It is who you are attracted to or who you love. Sexual orientation describes an enduring pattern of attraction and the inclination or capacity to develop intimate, emotional, and sexual relationships with other people. Sexual orientation is usually quantified in terms of gender—both an individual’s own gender and the gender(s) of the people to whom that person is attracted to. Categories for sexual orientation include straight, gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer, pansexual, asexual, and questioning, among many others. These categories, like all of this terminology, are constantly evolving.

I ask you to break away from what might be a tendency to look at birth sex, gender identity, gender expression, and sexual orientation as binary—that somebody is either male or female, a man or a woman, masculine or feminine, straight or gay. The components of sexual and gender identity are not binary and are not easily defined by checking one of only two boxes, although many of us have been conditioned to view them as binary.

I also ask you to consider that the components just discussed (birth sex, gender identity, gender expression, and sexual orientation) are not aligned or associated with each other in any particular groupings. One should not assume that a person born male would naturally identify as a man, be masculine, and be attracted to women. Likewise, one should not assume a person born female would identify as a woman, be feminine, and be attracted to men. For cultural, political, religious, and personal reasons some might want this to be true, but it does not match the reality of the human population. Men and women can be masculine, feminine or somewhere in between. A man can be attracted to men or women or both, and a woman can be attracted to men or women or both. A person can be born male but identify as a woman and vice versa.

The diagram below indicates many, but not all, of the possibilities.